Dr David Bullen, Lecturer in Drama and Theatre

Historical Context

- Performed in 441 BCE in the City Dionysia, Athens’ major annual festival dedicated to the god Dionysus.

- Performed exclusively by men, with three actors sharing the character parts using masks and costume changes and a group of Athenian youths playing the chorus.

- It was performed alongside two other tragedies and a satyr play (a short, comedic play featuring the half-human, half-animal companions of Dionysus, the satyrs), also by Sophocles, and competed against two other sets of four plays (almost always three tragedies and a satyr play). None of the other plays performed alongside Antigone have survived.

- While it is often grouped with Sophocles’ other ‘Theban’ plays, Oedipus the King and Oedipus at Colonus, it was not originally connected to those plays – and while the action the play dramatizes is chronologically after the other two, Antigone was written first.

- The play is set in the mythical past but Thebes was a real city that was uncomfortably close to Athens – they were often at war with one another. While, at the time Sophocles wrote Antigone, Athens was governed by a kind of democracy, Thebes was ruled by aristocratic families.

Key Ideas

- When staging a translation of Antigone, whether you retain its ancient setting or recontextualise to another period or place, it is crucial that your audience understand who Antigone, Creon, and the chorus are. All play vital roles and investing in one at the expense of the others will create problems.

- The chorus is especially crucial: as citizens of Thebes, their presence not only provides a consistent throughline in contrast to the rise and fall of Antigone and Creon, but they make the play about more than just the struggle between those two personalities – it becomes about a community.

- As well as understanding who Antigone, Creon, and the chorus are, the audience needs to be able to grasp the relationships between them and what the power dynamics are that inform their interactions. Antigone’s resistance, for example, takes place from within Creon’s family – which distinguishes her from the chorus and helps explain why Creon is so enraged.

- Similarly, Creon may be dictator-like, but if you suggest this, be careful: his power depends on the support of the chorus, and at the end of the play it is the chorus who prompt him to change his mind. This stands to be a remarkable moment about leaders listening to the people.

- Remember that even when staging a translation, you’re producing an adaptation: there’s no other way to do it, because you need to bridge a two-and-a-half thousand year cultural gap. Every choice – from set and costume to acting – works to make the translated text meaningful to the audience.

- Of course, adaptations can be a lot of fun – and give license to tell the story in a new way – see below for some suggestions.

Things to Watch For / Think About

- How does a production construct Creon and Antigone? Do they seek to make one more sympathetic than the other? Think about how this manifests not just in way that say but in how they are dressed, how scenes are blocked, and how the production is promoted.

- Similarly, think about how the chorus are used in the production – are they prominent throughout or pushed off to one side during character dialogue? How do they provide a lens for you as an audience member to understand the action in different ways, or do you not connect with them? Either way, consider what impact they have on stage – are they ‘extras’, witnesses, eavesdroppers, active participants, or something else?

- How does the opening scene between Antigone and her sister Ismene influence how you think about Antigone and her decisions?

- What sustains your interest in Creon for the last part of the play? Do you enjoy watching a bad man get his comeuppance (if the production has framed him as ‘bad’)? Or do you find yourself feeling for him?

- Does the production make much of Creon’s turn to the chorus to ask what to do following the Teiresias scene? If so, what is the impact? If not, how does that change the way you think about Creon?

- What impact does the appearance of Eurydice, Creon’s wife, have on your understanding of Creon? Likewise, how does the news that he too lost a loved one in the battle – his other son – cause you to re-think what you know about him? Do you consider Creon’s actions differently when you’re made aware that he is, like Antigone, grieving?

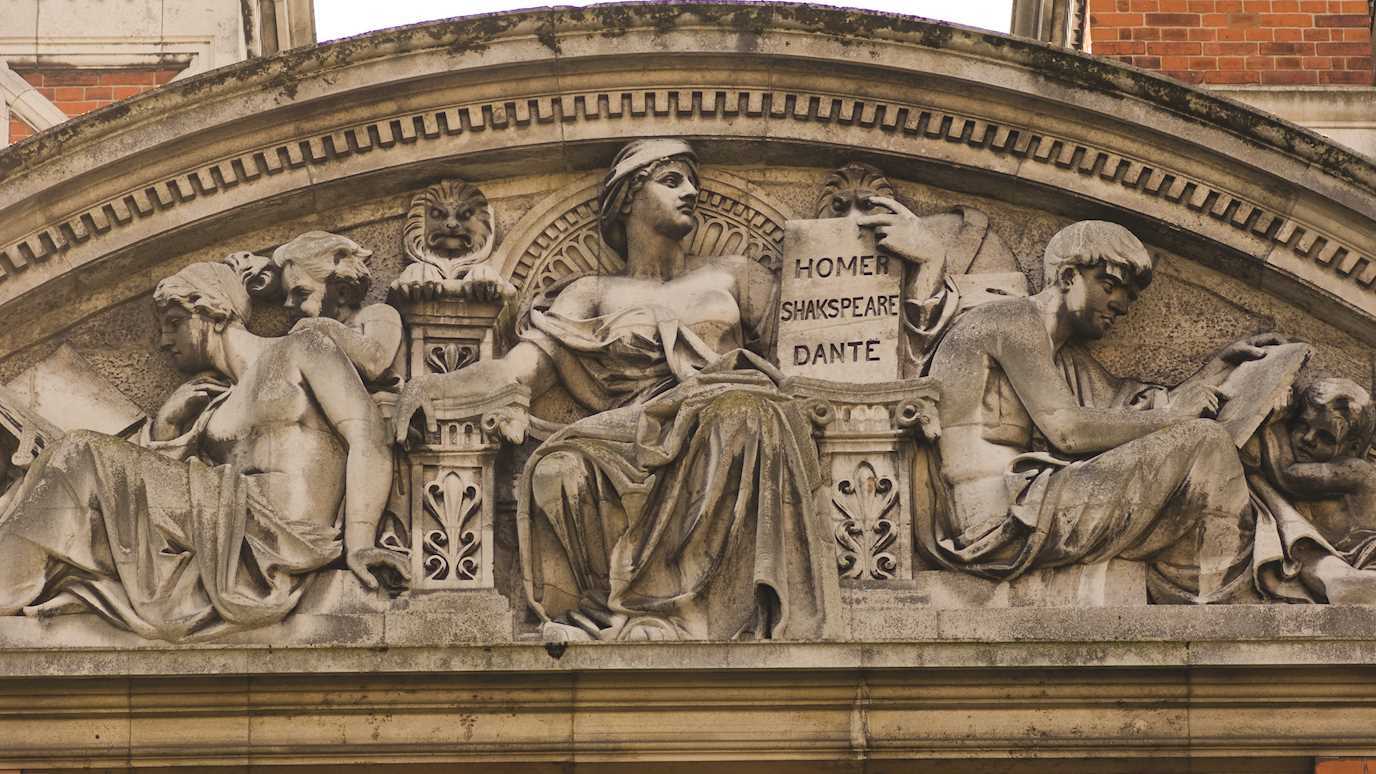

Legacy and Reception

- Antigone is one of the most discussed and performed plays in history, with lots of modern productions across the world

- Some of the most prominent philosophers of the past and present – from G. W. F. Hegel to Judith Butler – have used Antigone to think through complex ideas. Many of these are referenced in Anne Carson’s literary adaptation Antigonick.

- There’s a history of adapting this play to think about dictatorship, repression, and resistance. Both Bertolt Brecht and Jean Anouilh adapted the play in their responses to the Nazi regime. The Island (1973) by Athol Fugard, John Kani, and Winston Ntshona imagines Apartheid-era South Africa prisoners rehearsing Antigone – this was inspired by a true story involving Nelson Mandela when he was imprisoned on Robben Island.

- In 2017, novelist Kamila Shamsie published Home Fire, which re-imagined Antigone and her siblings as twenty-first century British Muslims living amidst a culture of rising state sanctioned Islamophobia. Playwright Inua Elams pursued a similar concept in his 2022 adaptation, which premiered at the Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre in London.

- Another exciting adaptation, written by Lulu Raczka and focused on the relationship between Antigone and Ismene, was staged at the New Diorama Theatre in 2020.

Other Resources

You can watch the National Theatre of Great Britain’s 2012 production online – now retroactively known as the ‘Two Doctors’ Antigone because it stars Christopher Ecclestone as Creon and Jodie Whittaker as Antigone, both of whom have played the title role in Doctor Who. You have access via the NT at Home site or Drama Online.

You can watch the Actors of Dionysus, who have been working exclusively with ancient Greek drama for almost 30 years, stage Antigone outdoors here. (Link: https://vimeo.com/manage/videos/226384843)

When looking for a translation, generally don’t go back further than 1990 if possible. If you’re interested in this text as a piece of theatre, look for a translation by a playwright – Timberlake Wertenbaker’s is great.

Further Reading and Listening

Helen Morales, Antigone Rising

David Stuttard (ed), Looking at Antigone

BBC In Our Time’s episode on Antigone https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m0015lwj

For inspiring adaptations that do interesting things with the play, see Anne Carson’s Antigonick, Lulu Raszca’s Antigone, Moira Buffini’s Welcome to Thebes, and Fugard, Kani, and Ntshona’s The Island.