Professor Elizabeth Schafer, Professor of Drama and Theatre Studies

Historical Context

- In the Elizabethan period English theatre makers were just beginning to make the transition to permanent, purpose-built playhouses.

- Only male players performed on the Elizabethan stage, so all female characters were played by men and boys.

- The Globe playhouse, which was built in 1599, looked structurally like the nearby bear baiting house.

- Actors – or players – were on a par with rogues and vagabonds in the social hierarchy. Legally they needed a powerful aristocrat to endorse them, to give them protection from prosecution; for example, for part of his career, Shakespeare worked for the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, a company protected by the Queen’s cousin, Henry Carey, Lord Hunsdon.

- It was understood that playhouse audiences spread diseases and so the playhouses were closed by the authorities when plague deaths in London reached a certain level. Companies sometimes then went on tour, which carried the risk they might spread plague.

- The light shared by performers and audience was provided by daylight in the outdoor playhouses and by candles in the indoor playhouses. Because candles needed to be trimmed, some plays written for indoor playhouse have obvious break points when the candles can be attended to.

- Queen Elizabeth would not attend a public playhouse. If she wanted to see a performance, it would be brought to her at court.

- Some Elizabethan plays suggest that in the public playhouses audiences enjoyed brash spectacle, battles, drums and trumpets.

- Audiences, especially the groundings, who stood in the yard around the stage, could be rowdy and they were very close to the performers. This could be a challenge if audiences became unruly. ‘Working’ the audience, interacting with them, observing them and responding to them was a very important skill for any player. These skills would also help any players – like Shakespeare – who also wrote plays.

- Sumptuary laws specified what kinds of clothes men and women in different social spheres were allowed to wear. This meant that in the playhouse costume communicated a lot about a character. Costumes were sometimes valuable hand-me-downs donated by aristocrats.

Key Ideas

- The sense of scene location in Shakespeare’s playhouse was created by words, not by spectacle; it was verbal rather than visual.

- The stage was large with the audience on 3 sides and visible to each other; this is an anti-illusionistic playing space and today we might call this kind of theatre ‘Brechtian’.

- There were two large pillars onstage.

- The groundlings who were standing in the yard could move around and change position easily.

- There was a gallery, which sometimes had musicians in it but which could also be used for performances.

- Performances were in what was, in the Elizabeth period, modern dress.

- The way Shakespeare presents the Countess Olivia’s garden in Twelfth Night exemplifies the anti-illusionistic dramaturgy of his plays because the garden location is so fluid. Olivia’s garden shifts and morphs into what is essentially a public space without any lines indicating that this is happening.

Things to Watch For / Think About

- A good way to get some sense of the demands that the public playhouse made on a performer is to mark out the stage – roughly 11 yards or strides by 9 – add something representing the pillars, and try playing different kinds of sequences from plays; for example a soliloquy contrasted with a scene with a large number of people (such as the opening of King Lear). In terms of connecting with the audience, performers needed to be resourceful, versatile, resilient and able to respond to the moment.

- If you can get to a live production at Shakespeare’s Globe or Shakespeare North, watch the audience as well as the performers (and remember that for some sections of the audience you are part of the ‘show’).

- Elizabethan Playhouses can be found vividly, if not always accurately, represented in films: for example, the representation of the Rose Playhouse in Shakespeare in Love offers a lot of performance/ audience insights but the Queen would not have visited a public playhouse.

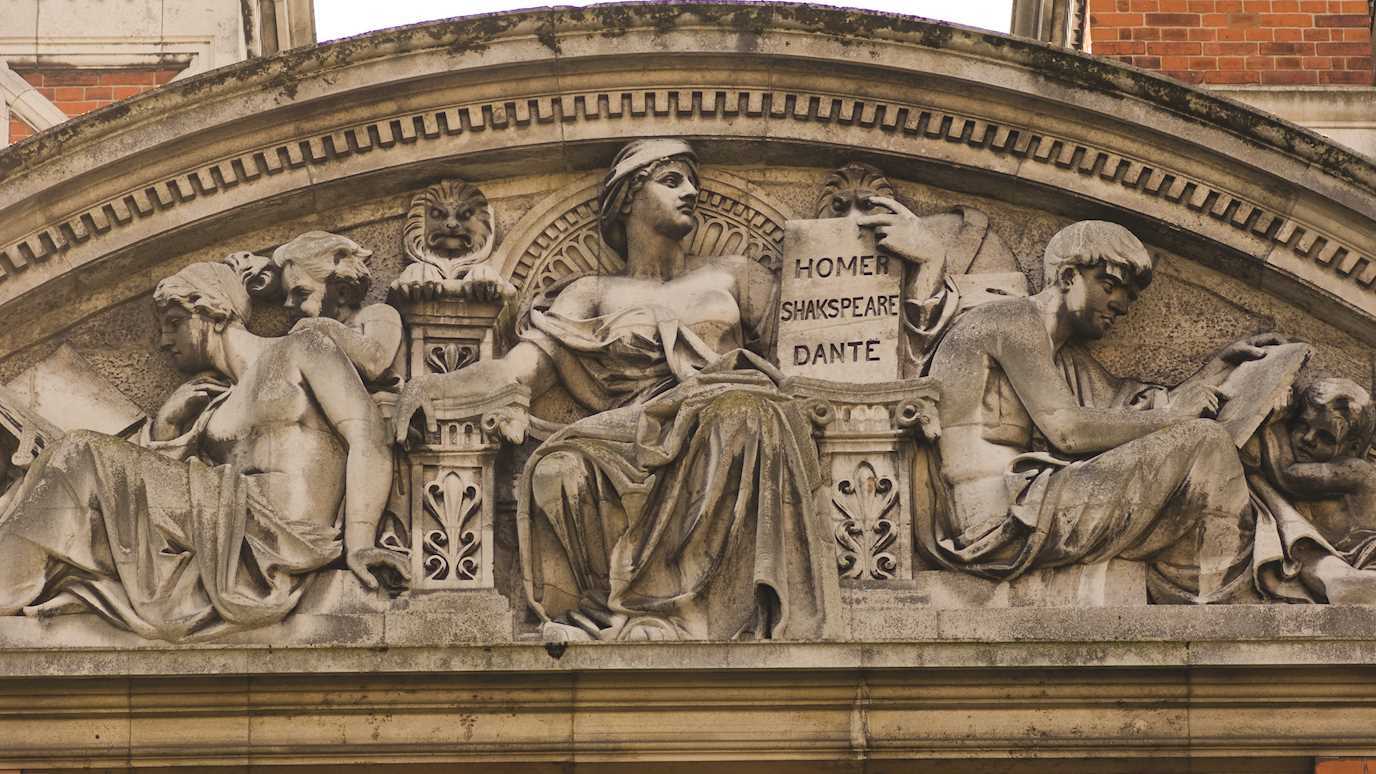

Legacy and Reception

- Many plays that were written to be performed in Elizabethan Playhouses – such as A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Romeo and Juliet, As You Like It, Twelfth Night, Much Ado About Nothing – are still popular today but they are rarely performed in the kind of theatre space they were written for. Shakespeare always knew which playhouse his plays would be first performed in and it is likely that his knowledge of the playhouse - as a player as well as a playwright – influenced his dramaturgy.

- After the Restoration in 1660, theatres began to move their performance area behind a proscenium arch, and the relationship between performer and audience changed; for example, soliloquies worked very differently; illusionistic scenery, especially using ‘flats’, became more viable; the fourth wall was beginning to come into existence.

- With the rise of Realism and Naturalism in the nineteenth century, performances often became more grounded in illusionism. This was then carried much further in realistic film and television.

- At the end of the nineteenth century, some theatre makers such as William Poel began to argue that early modern plays worked best in a performance space that evoked their original performance conditions. Later in the twentieth century many started experimenting with Elizabethan and Jacobean style playhouse configurations. As well as Shakespeare’s Globe – the main theatre and the Sam Wanamaker theatre – and Shakespeare North, there are early modern style playhouses elsewhere, such as the American Shakespeare Center, Staunton, Virginia, which has a Blackfriars style playhouse or the New Fortune Theatre at the University of Western Australia in Perth.

Other Resources

- Eric Rasmussen and Ian de Jong, ‘Shakespeare’s Playhouses’ https://www.bl.uk/shakespeare/articles/shakespeares-playhouses

- Interviews with actors who have performed in the reconstructed Shakespeare’s Globe https://www.shakespearesglobe.com/discover/ask-an-actor/

- A range of images of Shakespeare’s Globe are at https://www.shakespearesglobe.com/discover/blogs-and-features/2022/06/12/25-years-of-thiswoodeno/

- Blog on ‘Building Shakespeare’s Globe’ by Matt Truman https://www.shakespearesglobe.com/discover/blogs-and-features/2017/06/12/building-shakespeares-globe/

Further Reading and Watching

For interviews with practitioners and reflections by scholars on how Shakespeare’s Globe can work see:

- Farah Karim-Cooper and Christie Carson, Shakespeare's Globe: A Theatrical Experiment, Cambridge University Press, 2008.

For a discussion centred on how original performances could have worked see

- Peter Thomson, Shakespeare’s Theatre, 2nd edition, Routledge, 1992 (particularly useful in relation to Hamlet, Twelfth Night and Macbeth)

Most of the productions at Shakespeare’s Globe are recorded and can be accessed online. These productions, especially those claiming to be ‘original practices’, that is, seeking to resurrect the performance practices of Shakespeare’s day, often reveal a great deal about how the playhouse works; however, Shakespeare’s Globe is an imaginative reconstruction. Some features (toilets, exit signs, the yard’s concrete floor) are clearly not ‘original practices’ but geared up to modern theatre health and safety regulations.